What Records Can Parents Legally Demand After an Incident (FERPA + Footage)?

Table of Contents Click to Expand 1. Audio 2. Definition 3. Video 4. Core Thesis 5. Case Pattern Story 6. SANI Connection 7. Discipline Explanation

1. Audio

2. Definition

3. Video

4. Core Thesis

9. Action Steps

10. FAQs

11. Call to Action

12. Sources

13. Signature

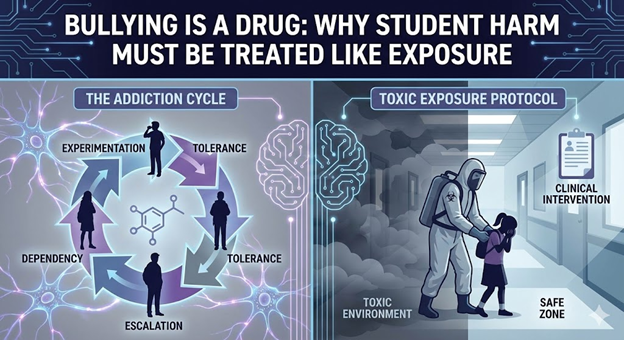

Bullying-as-a-Drug is a behavioral addiction framework that reframes student-on-student harm not as isolated misbehavior but as a progressive power addiction cycle characterized by: initial experimentation with harm, reinforcement through institutional non-response, tolerance development requiring escalation to achieve the same reward, dependency on power dynamics for social status, withdrawal symptoms when power is threatened, and enablement by adults who fail to intervene. Under this framework, student harm must be treated like toxic exposure—requiring immediate removal from the harmful environment, comprehensive safety planning, pattern documentation, and institutional accountability for allowing the addiction cycle to develop and persist.

Bullying is not misbehavior—it is a behavioral addiction to power. The Student Advocacy Network Institute, a Policy-Driven Student Safety Agency, was founded on this core principle: when schools treat bullying as “kids being kids,” they enable an addiction cycle that escalates predictably and causes neurobiological harm comparable to trauma exposure. We convert trauma into code by reframing student harm as toxic exposure that triggers mandatory removal, documentation, pattern analysis, and institutional accountability—just as exposure to asbestos, lead, or hazardous substances would. Selective enforcement IS discrimination because some students are removed from toxic exposure immediately while others are forced to endure repeated exposure until permanent harm occurs. This article provides the scientific, behavioral, and legal framework for treating student harm like the exposure event it actually is.

The Student Advocacy Network Institute was founded on a single, revolutionary premise: Bullying is a drug. As the nation’s first Policy-Driven Student Safety Agency, SANI operates at the intersection of addiction science, trauma neuroscience, and institutional accountability.

When a parent contacts SANI and says, “The bullying keeps getting worse,” we don’t ask, “What did your child do to provoke it?” We ask:

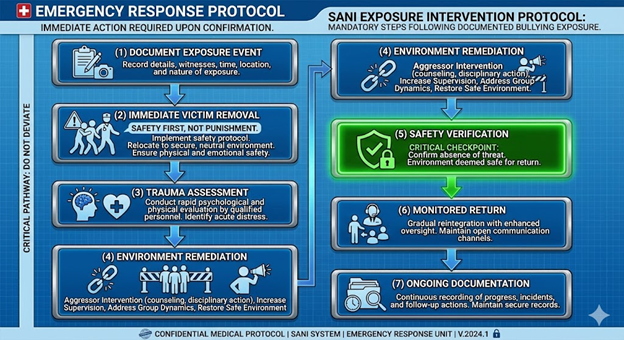

We convert trauma into code by translating the Bullying-as-a-Drug framework into enforceable safety protocols:

Exposure Documentation: We document each incident as an exposure event, not a “conflict.” Just as repeated lead exposure is cumulative and toxic, repeated bullying exposure is cumulative and neurologically damaging.

Immediate Removal Protocol: We demand that victims be removed from the toxic environment immediately—just as a child exposed to asbestos would be removed from the contaminated building. The victim does not return until the environment is proven safe.

Aggressor Intervention: We demand that aggressors receive addiction-informed behavioral intervention—not punishment alone, but interruption of the reward cycle that reinforces the addiction.

Institutional Accountability: We hold schools liable for enabling the addiction by failing to intervene, failing to document, and failing to recognize escalation patterns.

SANI treats student harm as both a school safety issue and a civil rights issue because the Bullying-as-a-Drug framework reveals how selective enforcement IS discrimination. When Black students, disabled students, or LGBTQ+ students are forced to endure prolonged exposure while white, non-disabled, or heterosexual students are removed after the first incident, the disparity is not just unfair—it is a civil rights violation that causes measurable neurobiological harm.

Bullying is a drug. Victims are exposed. Schools are enablers. And SANI is the enforcement agency that stops the cycle.

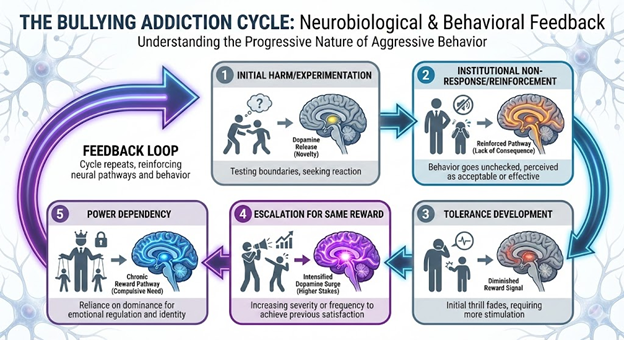

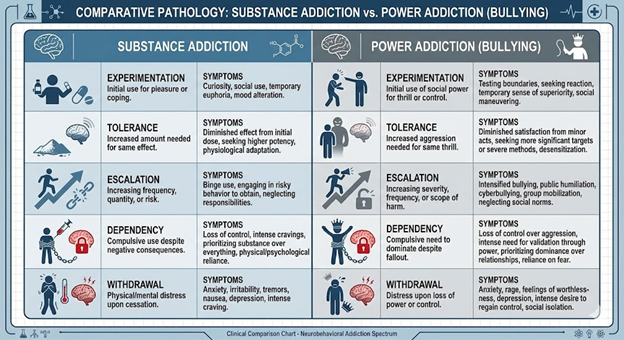

When an individual exerts power over another person and experiences no negative consequence, the brain releases dopamine—the same neurotransmitter involved in substance addiction, gambling addiction, and other behavioral addictions.

The reward pathway:

This is not conscious. It is neurobiological. The aggressor’s brain is being conditioned to seek power through harm.

Like substance tolerance, behavioral tolerance develops. The same action that initially produced a dopamine spike eventually produces a diminished response. The aggressor needs escalation to achieve the original high:

This is why bullying escalates. It is not because the victim “provokes” more—it is because the aggressor’s brain has developed tolerance and requires increased intensity to achieve the same neurochemical reward.

Over time, the aggressor’s social identity and self-concept become dependent on the power dynamic. Removing the victim or interrupting the behavior creates withdrawal symptoms:

This is why “separating the students” often fails. The aggressor doesn’t stop—they find a new victim. The addiction persists until the reward cycle is interrupted through intervention.

While the aggressor experiences addiction, the victim experiences toxic stress—a term used in trauma research to describe prolonged activation of the body’s stress response system.

Each bullying incident triggers the victim’s fight-flight-freeze response, releasing cortisol and adrenaline. Acute stress is adaptive. Chronic stress is toxic.

Effects of prolonged cortisol exposure:

These are the same neurobiological changes observed in children exposed to domestic violence, community violence, and chronic poverty. Bullying is exposure trauma.

Repeated exposure to harm that the victim cannot escape or control creates learned helplessness—a psychological state where the victim stops attempting to escape even when escape becomes possible.

Research by Martin Seligman (1967) demonstrated that animals exposed to inescapable shock eventually stopped trying to escape even when barriers were removed. Human victims of chronic bullying exhibit identical patterns:

This is not weakness. This is neurobiological adaptation to prolonged, uncontrollable threat.

Schools are institutional enablers of the bullying addiction cycle. They fail in predictable ways:

Schools treat each incident as isolated misbehavior. They don’t track patterns. They don’t recognize escalation. They don’t understand that the aggressor’s brain is being conditioned to seek power through harm.

Consequence: The addiction cycle continues unchecked.

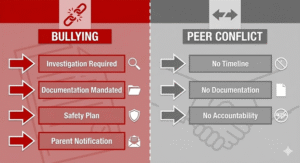

Schools deploy interventions designed for conflict (mediation, apologies, peer talks) to address addiction. This is equivalent to asking a heroin addict to “just talk it out” with their dealer.

Consequence: The aggressor learns to perform compliance (apologize, promise to stop) while continuing the behavior. The reward cycle is never interrupted.

Schools resist removing aggressors because of concerns about “lost instruction time,” “discipline disparities,” or “the aggressor’s right to education.” Meanwhile, the victim is forced to remain in the toxic environment.

Consequence: The victim absorbs compounding trauma while the aggressor’s addiction deepens.

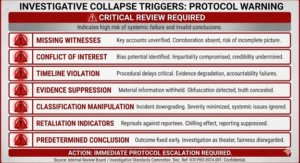

Without documentation, there is no visible pattern. Each incident appears minor. The escalation from verbal to physical to group-based is invisible in the record.

Consequence: Schools claim “this was the first serious incident” when, in fact, it was the tenth incident in an escalating pattern.

If we accept that bullying is exposure trauma, the intervention framework changes entirely.

Substance Exposure Analogy:

Bullying Exposure Protocol (What Should Happen):

This reframing eliminates victim-blaming. A child exposed to lead is not blamed for the exposure. A child exposed to bullying should not be blamed either. Exposure is the responsibility of the institution that allowed it.

Stop using the school’s language (“conflict,” “disagreement,” “peer issue”). Use exposure language:

Instead of: “My child is being bullied.”

Say: “My child is being exposed to repeated, escalating harm that is creating documented trauma symptoms. This is toxic exposure requiring immediate removal and safety intervention.”

Instead of: “The other student needs to stop.”

Say: “The aggressor is exhibiting a behavioral addiction pattern that requires intervention to interrupt the reward cycle. Informal talks will not address the neurobiological conditioning.”

This language forces the school to respond differently.

In your Master Timeline, frame entries as exposure documentation:

Date | Exposure Event | Severity | Cumulative Exposure | Neurobiological Symptoms |

9/12 | Verbal harassment (slurs) | Moderate | 1st exposure | Child reports fear |

9/15 | Physical (shoved into locker) | High | 2nd exposure | Sleep disruption begins |

9/20 | Threat + group intimidation | Severe | 3rd exposure | School refusal, crying |

9/22 | Physical assault | Critical | 4th exposure | PTSD symptoms, ER visit |

This format shows cumulative exposure and increasing harm—just like a toxicology report.

Send this communication:

Subject: Safety Protocol – Immediate Removal Required

Dear [Administrator]:

My child has been exposed to [NUMBER] documented incidents of harm over [TIME PERIOD], exhibiting an escalation pattern consistent with behavioral addiction cycles. Neurobiological symptoms include [LIST: hypervigilance, sleep disruption, academic decline, school refusal, etc.].

Under standard exposure protocols, my child must be immediately removed from the toxic environment until safety can be verified. This is not punishment—this is a safety measure.

I am requesting:

Failure to remove my child from documented toxic exposure constitutes deliberate indifference under [Title VI/IX/504] and creates liability for compounding harm.

Sincerely,

[Your Name]

Track and document symptoms in the Impact Documentation section of your Case File:

Sleep Disruption:

Hypervigilance:

Academic Decline:

Avoidance:

Emotional Dysregulation:

Somatic Symptoms:

Get these symptoms documented by medical and mental health professionals. These are objective evidence of exposure trauma.

Schools often ask: “What do you want us to do?”

Respond:

“The aggressor requires behavioral intervention that interrupts the reward cycle:

Informal talks, apologies, and peer mediation do not address addiction. They enable it.”

When the school says, “We talked to them and they promised to stop,” respond:

“That response reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the behavior. Bullying operates like addiction:

Your informal talk did not interrupt the reward cycle. It likely reinforced it by demonstrating that consequences remain absent. The aggressor’s brain has been conditioned to seek power through harm. This requires evidence-based intervention, not conversation.”

If the school fails to act, the exposure framework strengthens legal claims:

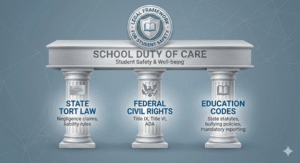

Negligence: The school had a duty to protect your child from foreseeable harm. Repeated exposure to documented harm is foreseeable. Failure to remove your child from the toxic environment is a breach of duty. The neurobiological harm (documented by medical professionals) is the damage.

Deliberate Indifference (Civil Rights): The school had actual notice of repeated exposure. Their response (informal talks, delay, inaction) was clearly unreasonable. The harm created a hostile educational environment. Under Title VI/IX/504, this is deliberate indifference.

Educational Malpractice / FAPE Violation: If your child has an IEP or 504 Plan, the school’s failure to provide a safe learning environment may violate their obligation to provide a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). Trauma exposure directly impairs access to education.

“Bullying is a drug” is a metaphor, but the neurobiological mechanisms behind it are real. Neuroscience research on behavioral addiction, reward pathways, and power dynamics shows that exerting power over others activates the same dopamine reward systems involved in substance addiction. Bullying behaviors often display addiction-like patterns such as tolerance, escalation, dependency, and withdrawal. The language is illustrative, but the brain science is well-established.

Punishment alone does not interrupt the reward cycle. The aggressor’s brain has been conditioned to associate harm with dopamine release. While punishment introduces a cost, the behavior persists if the reward remains strong and no alternative pathways to status or power are provided. Effective intervention requires removing access to the reward, offering healthier pathways to power or recognition, and disrupting group dynamics that reinforce the behavior.

Removal is a safety protocol, not a punishment. When a child is exposed to a toxic substance, we remove them from the contaminated environment to prevent harm—not because they did anything wrong. The same principle applies to bullying exposure. Removal may include online learning, alternative classroom placement, temporary transfer, or flexible scheduling. The goal is to stop ongoing harm while the environment is being addressed.

Exposure trauma can be documented through medical and mental health professionals. Pediatricians may document sleep disruption, somatic complaints, or behavioral changes. Therapists can diagnose anxiety, PTSD symptoms, school refusal, or trauma responses. Psychiatrists may prescribe medication for anxiety or depression linked to school-based trauma. School counselors or psychologists may document academic decline or social withdrawal. These records collectively establish evidence of harm caused by repeated exposure.

Yes. Under negligence and deliberate indifference frameworks, schools can be held liable when they repeatedly fail to intervene despite documented harm. Liability is created when the school had notice of a pattern, escalation was foreseeable, the response was clearly unreasonable, and the victim suffered measurable harm. Framing the school as an “enabler” uses addiction language to describe deliberate indifference.

Schools have both the authority and obligation to remove students who pose safety threats. Suspension, expulsion, and alternative placements are legally permissible when student safety is at risk. An aggressor’s right to education does not override a victim’s right to a safe learning environment. Prioritizing the aggressor’s access to a specific classroom over another student’s safety may violate civil-rights protections and create legal liability.

Yes. The addiction and exposure framework applies to verbal, physical, and cyberbullying. Verbal bullying is reinforced through social dominance and peer reactions, physical bullying through displays of power and fear, and cyberbullying through viral humiliation and perceived anonymity. All forms create dopamine-driven reward cycles for the aggressor and exposure trauma for the victim.

If you want student harm treated like a school safety and civil rights issue—start with SANI at https://saninstitute.net

The Student Advocacy Network Institute (SANI) is a national research, accountability, and discipline institute founded by Bullying Is A Drug to define, document, and address institutional failure in K–12 education—treating student harm as a school safety and civil rights issue.

Explore the Institute:

https://saninstitute.net

A fifth-grader pushes a classmate on the playground. A teacher sees it but does nothing—assumes it’s rough play. The aggressor feels a rush: power without consequence.

Week 2: The aggressor pushes the same student again, this time harder. Still no adult intervention. The victim stays quiet, fearing retaliation. The aggressor’s brain registers: power = reward, no consequence = safety to continue.

Week 4: Pushing no longer delivers the same thrill. The aggressor needs escalation. He starts verbal taunts alongside the physical aggression. Other students laugh. The reward intensifies: power + social status.

Week 6: The victim reports to a teacher. The teacher tells both students to “work it out” and “be kind to each other.” The aggressor learns: adults will not stop me. The victim learns: reporting makes it worse.

Week 8: The aggressor recruits two friends. Now it’s a group. The victim is cornered in the bathroom, threatened, shoved into the wall. The aggressor feels euphoria—maximum power, maximum social dominance, zero adult consequence.

Week 10: The victim stops coming to school. The aggressor experiences withdrawal—the power source is gone. He needs a new target. He finds one.

This is not a discipline problem. This is an addiction cycle:

The school treated this as “boys being boys.” They intervened with informal talks, conflict resolution, and peer mediation. None of it worked—because you cannot mediate an addiction. You cannot resolve a power dependency through conversation.

The victim’s parents finally remove their child from the school. Medical records document: PTSD, anxiety disorder, school refusal, academic regression. Therapy notes describe “trauma response consistent with prolonged exposure to threat and helplessness.”

This is exposure trauma—the same neurobiological harm caused by prolonged exposure to domestic violence, community violence, or environmental toxins. The child’s brain was repeatedly flooded with cortisol and adrenaline. Neural pathways associated with safety and learning were damaged. The harm is measurable, documented, and permanent.

The school’s response? “We had no idea it was this serious. Kids have conflicts.”

They didn’t recognize the addiction cycle. They didn’t treat the harm as exposure. They didn’t remove the victim from the toxic environment. They enabled the aggressor’s addiction and allowed the victim to absorb compounding harm.

This happens thousands of times per day in American schools.

Table of Contents Click to Expand 1. Audio 2. Definition 3. Video 4. Core Thesis 5. Case Pattern Story 6. SANI Connection 7. Discipline Explanation

Table of Contents Click to Expand 1. Audio 2. Definition 3. Video 4. Core Thesis 5. Case Pattern Story 6. SANI Connection 7. Discipline Explanation

Table of Contents Click to Expand 1. Audio 2. Definition 3. Video 4. Core Thesis 5. Case Pattern Story 6. SANI Connection 7. Discipline Explanation

Table of Contents Click to Expand 1. Audio 2. Definition 3. Video 4. Core Thesis 5. Case Pattern Story 6. SANI Connection 7. Discipline Explanation